“Time spent on reconnaissance is rarely wasted” is an axiom generally attributed to the sixth century Chinese general and strategist Sun Tzu, although others claim Napoleon, Rommel, Montgomery and even Custer said it. It’s likely to be Sun Tzu for many successful generals have followed his dicta and aphorisms and very unlikely to be Custer, one of the worst commanders in history, who would have done well to heed the advice of his scouts. In naval warfare the frigate, which Nelson called “the eyes of the fleet”, was built for scouting, speed and manoeuvrability – just like the Ferret.

Together with the tactical advantage of height, there is an unceasing quest to see beyond the other side of the hill: to discover the dispositions of the enemy, deduce his intentions and to relay this information to the force commander.

“Within armoured forces there are two schools of thought as to the most appropriate means of gaining this intelligence: by force or by stealth. The former requires a well-armed vehicle capable of fighting opposing tanks on almost equal terms, whereas the latter requires a fast, highly agile vehicle with superior surveillance equipment, but only sufficient firepower for self-defence”. This description comes from the excellent book on the Scorpion reconnaissance vehicle (Osprey, 1995) but applies equally to its predecessor: the Ferret.

The British army has traditionally advocated reconnaissance by stealth. The Daimler Dingo scout car served throughout the army and was crucial in policing the British Empire. Closer to home, wheeled liaison & reconnaissance vehicles like the Ferret and APCs (such as the Humber Pig and the Alvis Saracen) were used where tracked tanks were politically unacceptable, for example in urban environments supporting the civil power and in BAOR.

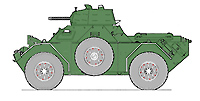

The Ferret was developed as successor to the Dingo for the same liaison role and reconnaissance by stealth. The low silhouette, particularly of the Mk 1 Ferret, helped make it hard-to-detect along the horizon or in thick brush and vegetation where it could hide easily. The Ferret also possessed the operating speeds – including strong off road performance, agility and protection required of it as a light scout vehicle.

Three Ferrets were attached to each tank squadron, forming a reconnaissance troop which scouted forward of the heavy armour to locate the position of the enemy. The last major British use of Ferrets was in Operation Granby, during the 1991 Iraq War. Read more about the Ferret and see the detailed specification list here. An explanation of the radios fitted in the Ferret, as appropriate for role, is given here.

Aside of political considerations amongst civilian populations, the ‘wheeled versus tracked’ argument has been debated by the military for tactical reasons. On the right-hand sidebar, you will find an article setting out the historical views, and the future thinking for wheeled armour in the British Army 2020 vision. Three armoured infantry brigades will now be centred round a single location (Salisbury Plain training area) with the army retaining a UK-wide presence in seven major centres. The future wheeled vehicle is likely to be the Boxer eight-wheel armoured utility vehicle, seen here in promotional colours.

- Sun Tzu’s quotes from The Art of War – The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting

- Military maxims of Napoleon – Morale is to the physical as three is to one

- von Clausewitz‘s Vom Kriege and Chapter 1 here – war is a continuation of politics by other means

- Some historians say the six week Battle of Kursk was the largest ever tank conflict, yet the engagements during Desert Storm, the first Gulf War, was more intense, occurred over a four-day time frame, involved more armour (7,818 tanks as opposed to 6,528 at Kursk) and was far more powerful than anything that had ever been seen before on a battlefield.

[taken from Hugh McManners’ blog 10 March 2017. Please also consider supporting the Scars of War Foundation].

In two sentences, Max Hastings summarises the true nature of war ‘I thought of war as a peerless adventure, which indeed it is for some thoughtless young men. Yet in Vietnam I grew to understand that whatever the compensations of battlefields for soldiers, there are none for their millions of victims, especially women, who are sexually vulnerable to any man with a gun.’ The Times Magazine, 9th Sept. 2018, page 15. I would add that war changes and often destroys serving soldiers too. Their suicide rates as veterans are higher than the general population. [Please support Combat Stress and the Scars of War Foundation

Well concealed in undergrowth

Mk 2/3 18 EA 73 of the

17th/21st Lancerson reconnaisance, BAOR